Analytical jurisprudence is the general name for the

approach to Jurisprudence which concern itself mainly with classification of

legal principles and rules and with analysis of the concepts, relationships

woeds and ideas used in legal system such as Person, Obligation, Right, Duty,

Act, etc. It is mainly associated with Positivism, the approach to law which

concerns itself with positive law i.e., legal system and rules actually in

force distinct from ideals systems or law which should be. Analytical

Jurisprudence though fore – shadowed by Thomas Hobbes, is chiefly associated

with Jeremy Bentham and Jhon Austin. It has been extensively developed in

England notably by Markby, Holland, Salmond, Hart, etc. in the continent by Hans

Kelson and U.S.A. mainly by John Chipmin Gray, Oliver Wendell Holmes, etc.

Analytical School

The major premise of analytical school of jurisprudence is

to deal with law as it exist in the present form. It seeks to analyse the first

principle of law as they actually exist in the given legal system. The exponent

of analytical school of jurisprudence considered that the most important aspect

of law is its relation to the State. They treat law as a command emanating from

the sovereign, namely, the State. This school is therefore, also called the

imperative school. The advocates of this school are neither concerned with the

past of the law nor with the future of it, but they confine themselves to the

study of law as it actually exists i.e., positus. It is for this reason that

this school is also termed as the Positive School of Jurisprudence. Bentham and

Austin are considered to be the Austinian School of Jurisprudence. The school

received encouragement in United States from distinguished jurists like Gray,

Hohfeld and Kocourck and in the European continent from Kelson, Korkunov and

others.

Analytical School – Meaning

Analytical Jurisprudence which Sir John Salmond terms

Systematic Jurisprudence and C.K. Allen as Imperative Jurisprudence is that

approach of method which considers law as a body of actual interrelated

principles and not merele a haphazard selection of rule inextricably interwoven

with a transcendental Law of Nature. It seeks to define all laws, classify all

laws, discover the essential features of every law and get a yardstick by which

all laws can be measured. It mainly aims at reconstructing a scientifically

valid system by analyzing legal concept on the basis of observation and

comparison by reducing law into a logical fasion. Such an approach towards law

is described Analytical Jurisprudence. C.K Allen, ghowever, maintains that

since jurists of this School consider law as an imperative or command emanating

from a politically independent sovereign so the approach of these jurist may be

described as Imperative School of Jurisprudence. Analysis of legal rules,

concepts and ideas through empirical or scientific method is commonly described

Analytical Jurisprudence.

Jeremy Bentham (1748 – 1832)

Bentham was the son of a wealthy London Attorney. His genius was of rarest quality. He was a talented person having the capacity and acumen of a jurist and a logician. Dicey in his book ‘Law and Public opinion in 19th Century’, has sketched Bentham’s ideas about individualism, law and legal reforms which have affected the growth of English law in the positive direction. The contribution of the Jeremy Bentham to the English Law reforms can be summarised thus-

“He determined, in the first place, the principles on which reforms should be based.

Secondly, he determined the method i.e., the mode of legislation, by which reforms should be carried out in England.”

Jeremy Bentham’s View on Law

English law as it existed at the end of the 18th century,

when Bentham was still in his youth, had developed almost in a haphazard way as

a result of customs or modes of thought which prevailed at different period.

The laws which were then in existence were not enacted with any definite

guiding principles behind them. The law of England, like that of most countries

of contemporary Europe, had grown out of occasion and emergence. It is for this

reason that it is often said that in England law had in fact grown, rather than

been made.

Jeremy Bentham defined law “as an assemblage of signs declarative of a volition conceived or adopted by the Sovereign in a State, concerning the conduct to be observed in a certain case by a certain person or class of persons, who in the case in question are or are supposed to be subject to his power; such violation trusting for its accomplishment to the expectation of certain events which it is intended such declaration should upon occasion be a means of bringing to pass, and the prospect of which it is intended should act as a motive upon those conduct is in question”.

Bentham’s concept of law is imperative one i.e., law is an assembly of signs, declarations of violation conceived or adopted by Sovereign in a State. He believed that every law may be considered in the light of eight different aspects, viz. –

1. Source (law as the will of Sovereign).

2. Subjects (may be persons or things).

3. Objects (act, situation or forbearance).

4. Extent (law covers a portion of land on which acts have been done).

5. Aspect (may be directive or sanctional).

6. Force

7. Remedial State Appendages.

8. Expression.

Jeremy Bentham defined law “as an assemblage of signs declarative of a volition conceived or adopted by the Sovereign in a State, concerning the conduct to be observed in a certain case by a certain person or class of persons, who in the case in question are or are supposed to be subject to his power; such violation trusting for its accomplishment to the expectation of certain events which it is intended such declaration should upon occasion be a means of bringing to pass, and the prospect of which it is intended should act as a motive upon those conduct is in question”.

Bentham’s concept of law is imperative one i.e., law is an assembly of signs, declarations of violation conceived or adopted by Sovereign in a State. He believed that every law may be considered in the light of eight different aspects, viz. –

1. Source (law as the will of Sovereign).

2. Subjects (may be persons or things).

3. Objects (act, situation or forbearance).

4. Extent (law covers a portion of land on which acts have been done).

5. Aspect (may be directive or sanctional).

6. Force

7. Remedial State Appendages.

8. Expression.

Bentham’s Contribution

Bentham’s contribution to legal theory is epoch making. “The

transition from the peculiar brand of natural law doctrine in the work of

Blackstone to the rigorous positivism of Bentham represents one of the major

developments in the history modern legal theory.” He gave new directions for

law making and legal research.

“With Bentham came the advent of legal positivism and with it the establishment of legal theory as a science of investigation as distinct from the art of rational conjecture, Bentham laid the foundations of this new approach, but, far from containing the solution to problems involving the nature of positive law, his work was only the beginning of very long and varied, series of debates, which are still going on today.”

“With Bentham came the advent of legal positivism and with it the establishment of legal theory as a science of investigation as distinct from the art of rational conjecture, Bentham laid the foundations of this new approach, but, far from containing the solution to problems involving the nature of positive law, his work was only the beginning of very long and varied, series of debates, which are still going on today.”

Bentham’s Influence

Whatever may be the shortcomings of Bentham’s theory, which

every theory is bound to have, his constructive thinking and zeal for legal

reform heralded a new era of legal reforms in England. Legislation has become

the most important method of law making in modern times. In the field of

jurisprudence, his definition of law down the foundations of new schools. As

stated earlier, Austin owes much to Bentham.

John Austin is the founder of the Analytical School. He is

considered as the ‘father of English Jurisprudence.’ He was elected to the

Chair of Jurisprudence in the University of London in 1826. Then he proceeded

to Germany and devoted some time to the study of Roman Law at it was taken in

Germany. The scientific treatment of Roman Law there made him aware of the

chaotic legal exposition of law in his own country. He took inspiration from it

and proceeded to make scientific arrangement of English Law. The method which

he applied was essentially of English origin. He avoid metaphysical method

which is a German character.

Austin’s Approach towards

Jurisprudence

Austin’s approach towards Jurisprudence and Law is found in

his own work. ‘The Province of Jurisprudence Determined’. The function of

jurisprudence, in view of Austin, was to find out general notions, principles

and distinctions abstracted from positive system of law mature and developed

legal system of Rome and England. His first task, therefore, was to separate

‘positive’ law from positive morality and ethics. Positive law, according to

Austin, was the law as it is (Positus) rather than law as it ought to be with

which he was not at all concerned. His particular concept of law was, however,

imperative being the command of the sovereign. For ‘Every positive Law set by a

given sovereign to a person or persons in a state of subjection to its author’.

According to Austin ‘The science of jurisprudence is concerned with positive

law or with laws strictly so called, as concerned without regard to their

goodness or badness. The positive law is characterized by four elements

command, sanction, duty and sovereignty.’

Austin’s method – Analytical

The method, which Austin applied, is called analytical

method and he confined his his field of study only to the positive law.

Therefore, the school founded by him is called by various names – ‘analytical’,

‘positivism’, ‘analytical positivism’. Some have objected to all three terms.

They say that the word ‘Positivism’ was started by Auguste Comte to indicate a

particular method of study. Though this positivism, later on, prepared the way

for the 19th century legal thought, it does not convey exactly the same at both

the places. Therefore, the word ‘positivism’ alone will not give a complete

idea of Austin’s school. In the same way, ‘analysis’ also did not remain

confined only to this school, therefore, it alone cannot give a separate

identity to the school. ‘Analytical positivism’ too may create confusion. The

‘Vienna School’ in its ‘Pure Theory of Law’ also applies analytical positivism

although in many respect they vitally differ from Austin’s school. To avoid

confusion and to give clarity which is the aim of classification, Prof. Allen

thinks it proper to call the Austin’s school as ‘Imperative School’. This name

he gave on the bais of Austin’s conception of law )’Law is command’).

Austin Theory of Imperative Law

‘Law’ in its most comprehensive and literal sense is a rule

laid down for the guidance of an intelligent being by an intelligent being

having power over him. This excludes the ‘laws’ of inanimate objects (physics,

etc.) and the laws of plant or animal growth which are described by Austin as

law improperly so called’. Next, Austin recognizes the law of God or divine law

which he regards as ambiguous and misleading. Law properly so called is the

positive law, that is law set by men to men. These are of three types;

1. Laws set by political superiors to their subjects,

2. Laws set by men who are not political superiors, and

3. Rules improperly but by analogy termed law e.g., law of fashion or honour or rules of international law.

The law set by political superior is the law properly so – called and (b) and (c) are positive morality.

1. Laws set by political superiors to their subjects,

2. Laws set by men who are not political superiors, and

3. Rules improperly but by analogy termed law e.g., law of fashion or honour or rules of international law.

The law set by political superior is the law properly so – called and (b) and (c) are positive morality.

Austin Conception of Law

Austin defined law as “a rule laid for the guidance of an

intelligent being by an intelligent being having power over him.” He divides

law into two parts, namely, (1) Laws set by God for men, and (2) Human Law,

that is laws made by men for men. He says that positive morality is not law

properly so called but it is law by analogy. According to him the study and

analysis of positive law alone is the appropriate subject – matter of

jurisprudence. To quote him, “the subject – matter of jurisprudence is positive

law – law simply and strictly so called; or law set by political superior to

political inferiors.” The chief characteristics of positive law are command,

duty and sanctions, that is every law is command, imposing a duty, enforced by

sanction.

Austin, however, accepts that there are three kinds of laws which, though, not commands, may be included within the purview of law by way of exception. They are: -

1. Declaratory or Explanatory laws; These are not commands because they are already in existence and are passed only to explain the law which is already in force.

2. Laws of repeal; Austin does not treat such laws as commands because they are in fact the revocation of a command.

3. Laws of imperfect obligation; they are not treated as command because there is no sanction to them. Austin holds that command to become law, must be accompanied by duty and sanction for its enforcement.

Austin, however, accepts that there are three kinds of laws which, though, not commands, may be included within the purview of law by way of exception. They are: -

1. Declaratory or Explanatory laws; These are not commands because they are already in existence and are passed only to explain the law which is already in force.

2. Laws of repeal; Austin does not treat such laws as commands because they are in fact the revocation of a command.

3. Laws of imperfect obligation; they are not treated as command because there is no sanction to them. Austin holds that command to become law, must be accompanied by duty and sanction for its enforcement.

Austin’s Concept of Law

Austin’s Definition of Law; Law, in the common use, means

and includes things which cannot be properly called ‘law’. Austin defined law

as ‘a rule laid down for the guidance of an intelligent being by an intelligent

being having power over him.’

Law of 2 kinds: (1) Law of God, and (2) Human Laws: This may be divided into two parts: (1) Law of God – Laws set by God for men. (2) Human Laws – Laws set by men for men.

Two kinds of Human Laws, Human Laws may be divided into two classes;

1. Positive Law; These are the laws set by political superiors as such, or by men not acting as political superiors but acting in pursuance of legal rights conferred by political superiors. Only these laws are the proper subject – matter of jurisprudence.

2. Other Laws; Those laws which are not set by political superiors (set by persons who are not acting in the capacity or character of political superiors) or by men in pursuance of legal rights.

Analogous to the laws of the latter class are a number of rules to which the name of law is improperly given. They are opinions or sentiments of an undeterminate body of men, as laws of fashion or honour. Austin places International Law under this class. In the same way, there are certain other rules which are called law metaphorically. They too are laws improperly so called.

Positive Law as Command

The law properly so – called is the positive law depends upon political authority – the sovereign. Every rule, therefore, according to Austin is a command. So laws properly so called are a species of commands. If you express or intimate a wish that I shall do or forbear from some of your wish, the expression or intimation of your wish is a command. If I am bound by it, I lie under a duty to obey it. Command – duty are, therefore, correlative terms. Command further implies not only duty but sanction also.

Law is Command

Positive law is the subject – matter of jurisprudence, Austin says that only the positive law is the proper subject – matter of study for jurisprudence. “The matter of jurisprudence is positive law: law simply and strictly so called: or law set by political superiors to political inferiors.” Jurisprudence is the general science of positive law. The characteristics of law.

Command and Sanction

Sanction as an evil which will be incurred if a command is disobeyed and is the means by which a command or duty is enforced. It is wider than punishment. A reward for obeying the command can scarcely be called a sanction. A command embraces:

(a) A wish or desire conceived by a rational being to another rational being who shall do or forbear as commanded;

(b) An evil to proceed from the former to be incurred by the latter in case of non – compliance; and

(c) An expression or intimation of the will by words or otherwise.

Commands are of two species:

(a) Las or rules, and

(b) Occasional commands.

A command is a law or rules where it obliges generally to acts or forbearances of people. It is occasional or particular when it obliges to a specific individual for act or forbearance.

Law is a command which obliges a person or persons to a course of conduct. It requires signification and can, therefore, only emanate from a determinable source or author (a person or body of persons).

Laws proceed from superiors and bind and oblige inferiors. Superiors are invested with might: the power of affecting others with pain or evil and thereby of forcing them to conform their conduct to their orders.

Law of 2 kinds: (1) Law of God, and (2) Human Laws: This may be divided into two parts: (1) Law of God – Laws set by God for men. (2) Human Laws – Laws set by men for men.

Two kinds of Human Laws, Human Laws may be divided into two classes;

1. Positive Law; These are the laws set by political superiors as such, or by men not acting as political superiors but acting in pursuance of legal rights conferred by political superiors. Only these laws are the proper subject – matter of jurisprudence.

2. Other Laws; Those laws which are not set by political superiors (set by persons who are not acting in the capacity or character of political superiors) or by men in pursuance of legal rights.

Analogous to the laws of the latter class are a number of rules to which the name of law is improperly given. They are opinions or sentiments of an undeterminate body of men, as laws of fashion or honour. Austin places International Law under this class. In the same way, there are certain other rules which are called law metaphorically. They too are laws improperly so called.

Positive Law as Command

The law properly so – called is the positive law depends upon political authority – the sovereign. Every rule, therefore, according to Austin is a command. So laws properly so called are a species of commands. If you express or intimate a wish that I shall do or forbear from some of your wish, the expression or intimation of your wish is a command. If I am bound by it, I lie under a duty to obey it. Command – duty are, therefore, correlative terms. Command further implies not only duty but sanction also.

Law is Command

Positive law is the subject – matter of jurisprudence, Austin says that only the positive law is the proper subject – matter of study for jurisprudence. “The matter of jurisprudence is positive law: law simply and strictly so called: or law set by political superiors to political inferiors.” Jurisprudence is the general science of positive law. The characteristics of law.

Command and Sanction

Sanction as an evil which will be incurred if a command is disobeyed and is the means by which a command or duty is enforced. It is wider than punishment. A reward for obeying the command can scarcely be called a sanction. A command embraces:

(a) A wish or desire conceived by a rational being to another rational being who shall do or forbear as commanded;

(b) An evil to proceed from the former to be incurred by the latter in case of non – compliance; and

(c) An expression or intimation of the will by words or otherwise.

Commands are of two species:

(a) Las or rules, and

(b) Occasional commands.

A command is a law or rules where it obliges generally to acts or forbearances of people. It is occasional or particular when it obliges to a specific individual for act or forbearance.

Law is a command which obliges a person or persons to a course of conduct. It requires signification and can, therefore, only emanate from a determinable source or author (a person or body of persons).

Laws proceed from superiors and bind and oblige inferiors. Superiors are invested with might: the power of affecting others with pain or evil and thereby of forcing them to conform their conduct to their orders.

Command Exceptions

The proposition that all laws are commands must, therefore,

be taken with limitations for it is applied to objects which are not commands.

These exceptions are:

(a) Acts of the legislature to explain positive laws or which are declaratory of the existing laws only;

(b) Repealing statutes (which are revocations of commands);

(c) Laws of imperfect obligations without an effective sanction like rules of morality or rules of international law.

(a) Acts of the legislature to explain positive laws or which are declaratory of the existing laws only;

(b) Repealing statutes (which are revocations of commands);

(c) Laws of imperfect obligations without an effective sanction like rules of morality or rules of international law.

Theory of Sovereignty

Every positive law (or every law properly so – called) is

set by a sovereign person or a sovereign body to a member or members of independent

political society wherein that person or body is sovereign or supreme. In other

words, law is set by the sovereign to a person or persons who are in a state of

subjection to its author. The relationship subsisting between the superior and

rest of the given society is that of sovereign and subject. Generality of its

member must be in a habit of obedience to a determinate common superior.

Further the power of the sovereign is incapable of legal limitation.

Austin’s method of

Jurisprudence

Austin Method: analysis; This method can be applied only in

civilized societies. The name of this school – ‘analytical’ itself indicates

the method. Austin considered analysis as the chief instrument of

jurisprudence. Austin’s definition of law as the “command of the sovereign”

suggests that only the legal systems of the civilized societies can become the

proper subject – matter of jurisprudence because it is possible only in such

societies that the sovereign can enforce his commands with an effective

machinery of administration. Law should be carefully studied and analyzed and

the principle underlying therein should be found out. This method is proving

inadequate in modern times because jurisprudence is to solve many legal

problems which have arisen under changed conditions and it has to make

constructive suggestions also, but, at the time, when Austin gave his theory,

it helped in removing the confusion created by the abstract theories about the

scope and method of jurisprudence.

Austin’s Contribution;

Opening a New Era of Approach

These are the weaknesses of Austin’s theory pointing out by

his critics. Every theory has its limitations. Moreover Austin laid down many

of his propositions as deduced from English law as it was during his time. The

credit goes to Austin for opening an era of new approach to law. Even the

defects of his theory have been a source of further enlightenment on the

subject as Hart says, “But the demonstration of precisely where and why he is

wrong has proved to be constant source of illumination, for his errors are

often the mis – statement of truths of central importance for the understanding

of law and society’. One of his great critics, Olivercrona, also acknowledges

him as the pioneer of the modern positivists approach to law. Thus Austin made great

contributions to jurisprudence.

Austin’s method

Characteristic of English Jurisprudence; Austin’s Influence

The influence of Austin’s theory was great due to its

simplicity, consistency and clarity of exposition. That is why Gray remarked:

“If Austin went too far in considering the law as always proceeding from the

state, he conferred a great benefit on jurisprudence by bringing out clearly

that the law is at the mercy of the state.” Austin’s method in described as

characteristics of English jurisprudence. Prof. Allen says: “Far a systematic

exposition of the methods of English jurisprudence we will have to turn to

Austin.” The same is true about American also because Austin’s method was

greatly adopted there Austin’s theory had little influence in the continent for

the time being, and especially Germans, who always mixed metaphysical notions

with jurisprudence, were least appreciate of it. But of late years Austin has

received an increasing attention and respect from the jurists of the Continent

also. Germans also have come round the Austin’s view and many of them are

abjuring all ‘micnt positivisches Rechet.’

The latin analytical theories have improved upon Austin’s theory and have given a more practical and logical basis. Holland, though accepted the ‘command’ theory, made a slight variation. He says:-

“A law, in the proper sense of the term is, therefore, a general rule of human action, taking cognizance only of external acts, enforced by determinate authority.”

The latin analytical theories have improved upon Austin’s theory and have given a more practical and logical basis. Holland, though accepted the ‘command’ theory, made a slight variation. He says:-

“A law, in the proper sense of the term is, therefore, a general rule of human action, taking cognizance only of external acts, enforced by determinate authority.”

Later Jurists improved upon

his theory

Salmond and Gray further improved upon it and considerably

modified the analytical positivist approach. They differ from Austin in his

emphasis on sovereign as law giver. According to Salmond, the law consists of

the rules recognized and acted on by the court of justice. Gray defines law

what has been laid down as a rule of conduct by the persons ating as judicial organs

of the state. This emphasis on the personal factor in law, later on, caused the

emergence of the ‘Realist’ school of law.

The ‘Vienna School’ of law which is known as ‘pure Theory of Law’ (which we shall discuss later on) also owes to Austin’s theory.

Austin’s Followers

Austin’s influence upon English legal thought has been profound and continuing. He has been followed and emulated by many English jurists like Amos, Mark by, Holland, Salmond and Hart – the last of the two partly reject Austin’s concept of law. Both for Salmond and Hart positive law cannot be divorced from justice or morality. In the United States Gray, Hohfield and Kocourek and the distinguished exponents of Analytical School of Jurisprudence in one or the other way. In the continent Hans Kelson has been the most influential jurist whose theory of ‘pure law’ has attracted world wide attention.

Conclusion

At the end it can be concluded that, analytical school of jurisprudence consider that the most important aspect of law is its relation to the State. The School is, therefore also called the imperative school. The school received encouragement in United States from distinguished jurists like Gray, Hohfeld and Kocourck and in the European continent from Kelson, Korkunov and others.

Analytical Jurisprudence is that approach of method which considers law as a body of actual interrelated principles and not merely a haphazard selection of rule inextricably interwoven with a transcendental Law of Nature. It seeks to define all laws, classify all laws, discover the essential features of every law and get a yardstick by which all laws can be measured.

The ‘Vienna School’ of law which is known as ‘pure Theory of Law’ (which we shall discuss later on) also owes to Austin’s theory.

Austin’s Followers

Austin’s influence upon English legal thought has been profound and continuing. He has been followed and emulated by many English jurists like Amos, Mark by, Holland, Salmond and Hart – the last of the two partly reject Austin’s concept of law. Both for Salmond and Hart positive law cannot be divorced from justice or morality. In the United States Gray, Hohfield and Kocourek and the distinguished exponents of Analytical School of Jurisprudence in one or the other way. In the continent Hans Kelson has been the most influential jurist whose theory of ‘pure law’ has attracted world wide attention.

Conclusion

At the end it can be concluded that, analytical school of jurisprudence consider that the most important aspect of law is its relation to the State. The School is, therefore also called the imperative school. The school received encouragement in United States from distinguished jurists like Gray, Hohfeld and Kocourck and in the European continent from Kelson, Korkunov and others.

Analytical Jurisprudence is that approach of method which considers law as a body of actual interrelated principles and not merely a haphazard selection of rule inextricably interwoven with a transcendental Law of Nature. It seeks to define all laws, classify all laws, discover the essential features of every law and get a yardstick by which all laws can be measured.

H. L. A. Hart

H. L. A. Hart later addressed Austin. Hart liked Austin's theory of a sovereign, but claimed that Austin's Command Theory failed in several important respects. In the book The Concept of Law, Hart outlined several key points: Among the many ideas developed in this book are:

H. L. A. Hart later addressed Austin. Hart liked Austin's theory of a sovereign, but claimed that Austin's Command Theory failed in several important respects. In the book The Concept of Law, Hart outlined several key points: Among the many ideas developed in this book are:

A critique of John Austin's theory that law is the command of the sovereign enforced by the threat of punishment.

A distinction between the internal and external considerations of law and rules, close to (and influenced by) Max Weber's distinction between the sociological and the legal perspectives of law.

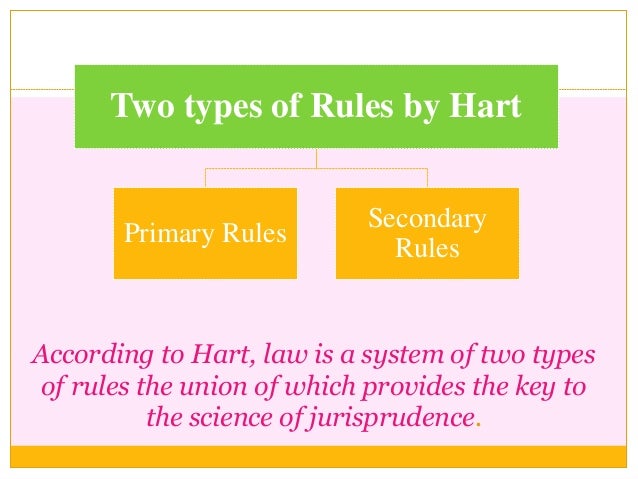

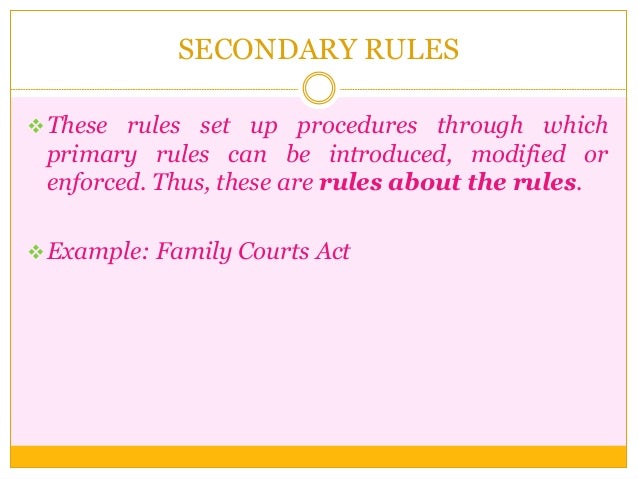

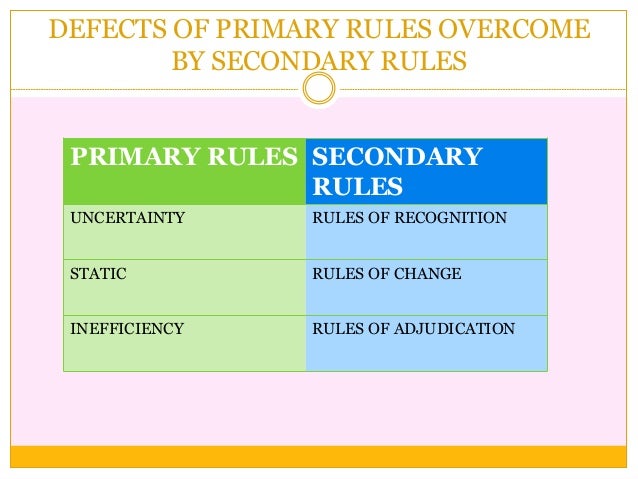

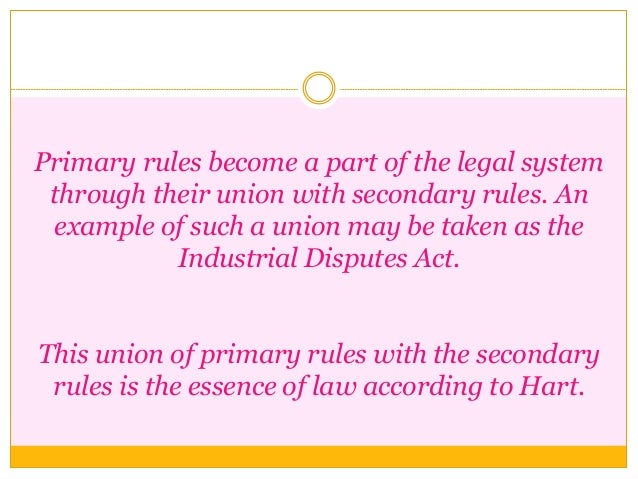

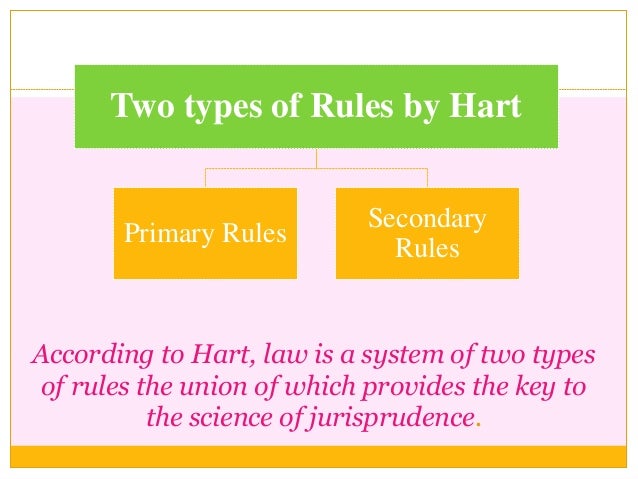

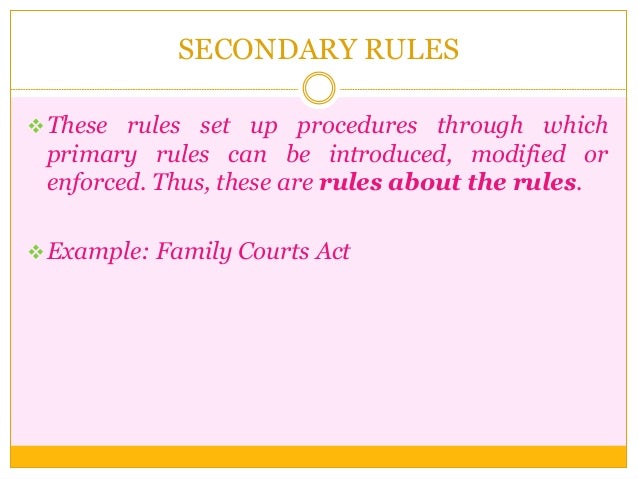

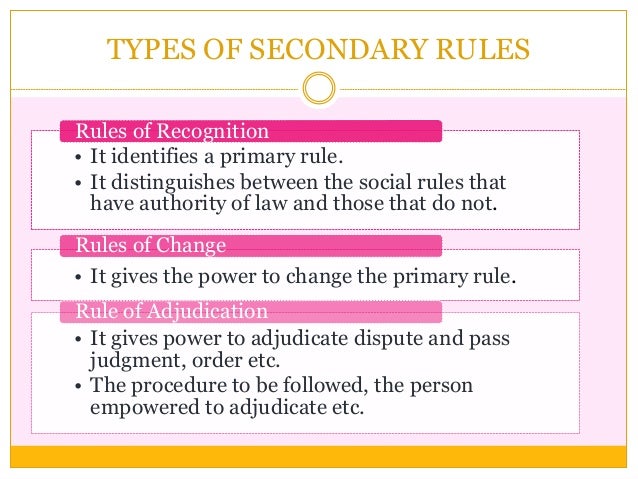

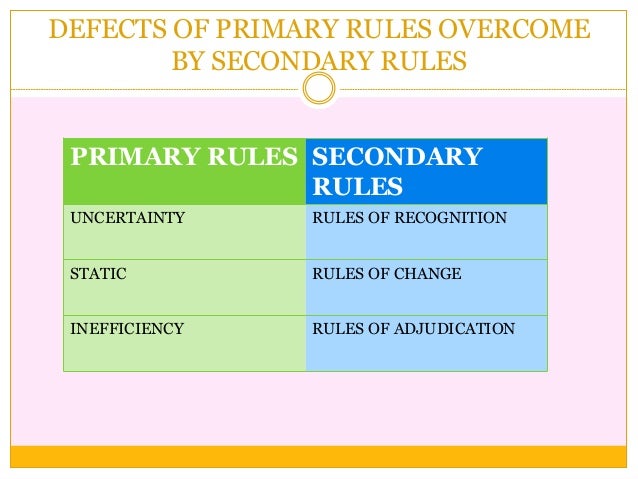

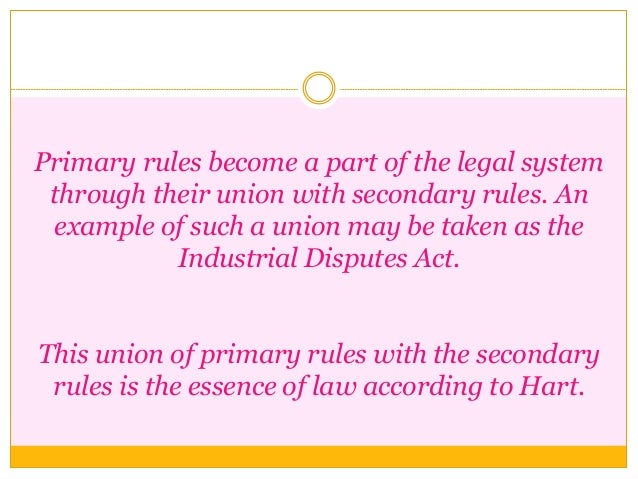

A distinction between primary and secondary legal rules, such that a primary rule governs conduct, such as criminal law, and secondary rules that govern the procedural methods by which primary rules are enforced, prosecuted and so on. Hart specifically enumerates three secondary rules; they are:

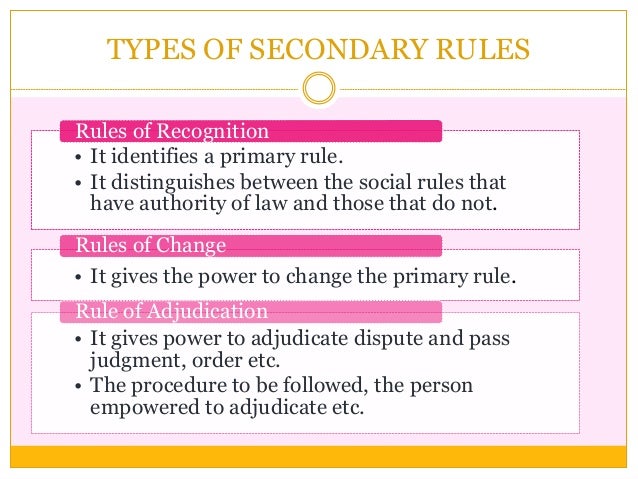

The Rule of Recognition, the rule by which any member of society may check to discover what the primary rules of the society are. In a simple society, Hart states, the recognition rule might only be what is written in a sacred book or what is said by a ruler. Hart claimed the concept of rule of recognition as an evolution from Hans Kelsen's "Grundnorm", or "basic norm."

The Rule of Change, the rule by which existing primary rules might be created, altered or deleted.

The Rule of Adjudication, the rule by which the society might determine when a rule has been violated and prescribe a remedy.

A late reply (1994 Edition) to Ronald Dworkin, who criticized legal positivism in general and especially Hart's account of law in Taking Rights Seriously (1977), A Matter of Principle (1985), and Law's Empire (1986).

A critique of John Austin's theory that law is the command of the sovereign enforced by the threat of punishment.

A distinction between the internal and external considerations of law and rules, close to (and influenced by) Max Weber's distinction between the sociological and the legal perspectives of law.

A distinction between primary and secondary legal rules, such that a primary rule governs conduct, such as criminal law, and secondary rules that govern the procedural methods by which primary rules are enforced, prosecuted and so on. Hart specifically enumerates three secondary rules; they are:

The Rule of Recognition, the rule by which any member of society may check to discover what the primary rules of the society are. In a simple society, Hart states, the recognition rule might only be what is written in a sacred book or what is said by a ruler. Hart claimed the concept of rule of recognition as an evolution from Hans Kelsen's "Grundnorm", or "basic norm."

The Rule of Change, the rule by which existing primary rules might be created, altered or deleted.

The Rule of Adjudication, the rule by which the society might determine when a rule has been violated and prescribe a remedy.

A late reply (1994 Edition) to Ronald Dworkin, who criticized legal positivism in general and especially Hart's account of law in Taking Rights Seriously (1977), A Matter of Principle (1985), and Law's Empire (1986).

Tags:

LLB Books (English)